Module 2. Bodily Responses to Food Allergens

Learning Objectives

After the module, students will be able to:

- Explain the differences between food allergies and food intolerances

- Describe a series of responses to food allergies in the human body

- Identify organs and body systems affected by allergic reactions to food

- Explain the definition of anaphylaxis and the physiological responses of anaphylactic shock

Module Content

- Definitions

- Food allergies vs. food intolerances

- Physiological responses to food allergens

- Symptoms of food-induced allergic reactions

- Diagnosis of food allergies

- Instructional video

- Additional information

- References

Definitions

(top)

Food allergies vs. Food intolerances

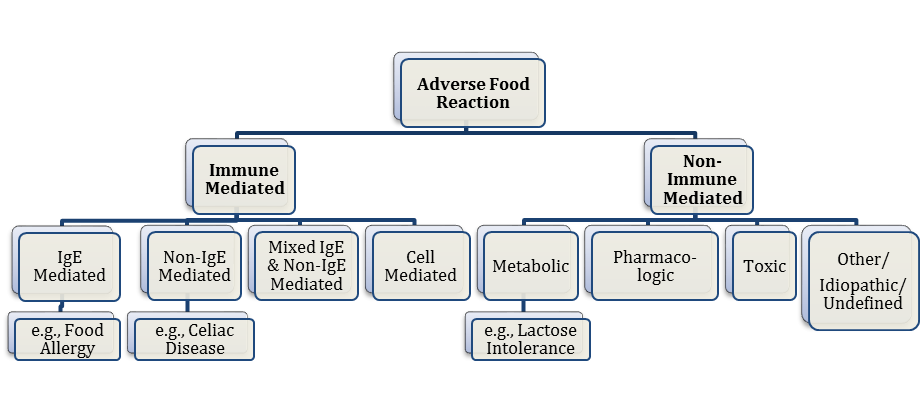

Both food allergies and food intolerances are types of adverse effects to food. How and why symptoms develop, however, differs.

A food allergy, "an abnormal response to a food, triggered by the body's immune system" (Boyce et al., 2010, p. S8), occurs when the body mistakenly recognizes some part of food as an antigen (FARE, 2014). Subsequently, immune responses will occur that involve IgE, and the body reacts with the systematic release of histamine.

Food intolerances, on the other hand, are non-immunologic adverse reactions to food due to lack of enzymes (e.g., lactose intolerance) or other irritant or toxic mechanisms. Two common food intolerances are lactose intolerance and gluten intolerance.

- Lactose Intolerance: individuals with lactose intolerance lack lactase, the enzyme that breaks down lactose, and experience excessive fluid production in the GI tract, resulting in abdominal pain and diarrhea. Similar intolerance can be observed when a person has hereditary fructose intolerance, the deficiency in fructose bi-phosphate aldolase, a liver enzyme (David, 2000). A person with this with hereditary fructose intolerance may experience an inability to digest the sugar fructose.

- Gluten intolerance: celiac disease is caused by an adverse reaction to gluten (FARE, 2014). If individuals with gluten intolerance accidentally ingest gluten, they experience severe abnormal pain and diarrhea (which can occur up to six hours after food is eaten). Other symptoms include bloating, abdominal discomfort or muscular disturbances, and bone or joint pain. Individuals with gluten intolerance should avoid wheat, barley, rye, oats and common cereal products that contain various amounts of gluten.

Figure 2.1. Types of adverse reactions to food. Adapted from "Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: Report of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel," by J. A. Boyce, 2010, The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 126, p. 10. Copyright 2010 by Elsevier Inc.

Table 2.1. Comparison of Food Allergies and Food Intolerances

| Food Allergy | Food Intolerance | |

|---|---|---|

| Body system | Skin Cardiovascular Gastrointestinal |

Gastrointestinal |

| Onset of symptoms | A few seconds to hours after ingestion | Slow onset |

| Immunological mechanism | Antibody (IgE) | None |

| Non-immunological mechanism | None | Lack of enzymes (e.g., lactase) |

| Amount of food to trigger a reaction | Dose varies depending on individuals, may be triggered by one molecule of food allergen | Dose varies depending on individuals |

| Note. Comparison of Food Allergies and Food Intolerances. Adapted from "Investigation of food allergy training and child nutrition professionals' knowledge and attitudes about food allergies (Doctoral dissertation)," by Y. M., Lee, 2012. Copyright 2012 by Kansas State University. | ||

(top)

Physiological Responses to Food Allergens

Immediate hypersensitivity reactions:

- IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reactions will be heightened when a person with a food allergy ingests food allergens.

- Symptoms may occur for up to two hours after ingestion of an allergen.

- Immediate responses are inflammatory responses due to the cross-linking of two IgE antibodies.

Delayed hypersensitivity reactions:

- Delayed hypersensitivity reactions are cell-mediated reactions that develop from 6 to 24 hours after ingestion of an offending food.

- Different immune cell types, such as t-cells, macrophages, and eosinophils, are involved in this type of reaction.

- Localized tissue damage may occur due to inflammation.

(top)

Symptoms of food-induced allergic reactions

Usually food allergy symptoms begin within two hours of eating a food. Symptoms may appear hours after eating, though this is rare (Chafen et al., 2010). Symptoms of food allergies can manifest in many systems, including the cutaneous, GI, and cardiovascular systems.

The most common symptoms are hives, wheezing and a hoarse voice (Table 2.2).

Other symptoms include the following:

- Abdominal pain

- Diarrhea

- Vomiting

- Stomach cramps

- Shortness of breath

- Runny nose

- Nasal congestion

- Lightheadedness or fainting

- Difficulty swallowing

- Itching of mouth, eyes, skin, throat and other areas

- Patches of itchy and scaly skin

- Swelling of face, lips, tongue and eyelids

Table 2.2. Symptoms of Food-induced Allergic Reactions:

| Target organ | Immediate symptoms | Delayed symptoms |

| Cutaneous | Erythema (redness of skin) Pruritus (itching) Urticaria (hives) |

Erythema (redness of skin) Flushing (blush ) Pruritus (itching) Eczematous rash (inflammatory condition with redness, itching, skin can become scaly, hardened) |

| Ocular | Pruritus Conjunctival erythema Tearing Periorbital edema |

Pruritus Conjunctival erythema Tearing Periorbital edema |

| Upper respiratory | Nasal congestion Pruritus Sneezing Laryngeal edema Dry staccato cough |

|

| Lower respiratory | Cough Chest tightness Wheezing Intercostal retractions |

Cough Wheezing |

| GI (oral) | Angioedema of the lips, tongue, or palate Oral pruritus Tongue swelling |

|

| GI (lower) | Nausea Colicky abdominal pain Vomiting Diarrhea |

Nausea Abdominal pain Vomiting Diarrhea Irritability and food refusal with weight loss (young children) |

| Cardiovascular | Hypotension Dizziness Fainting |

|

| Miscellaneous | Uterine contractions Sense of "impending doom" |

|

Note. Symptoms of food-induced allergic reactions. Adapted from "Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: Report of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel," by J. A. Boyce et al., 2010, The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 126, p. S19. Copyright 2010 by Elsevier Inc. |

||

(top)

Diagnosis of Food Allergies

According to National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) (2012), the following six steps are required to correctly diagnose food allergies:

- Detailed history - The most valuable tool for diagnosing a food allergy is gathering past history related to food allergy reactions. A series of questions are asked with regard to the following:

- The length of time between eating food and the allergic reaction.

- Foods associated with reactions

- The quantity eaten

- Have others have gotten sick from the same food?

- Were allergy medicines taken?

- Did the medicine help or not?

- Diet diary - A record of foods eaten, including whether an allergic reaction occurred or not.

- Elimination diet - Suspected foods associated with an allergy are removed from the diet to see if an allergic reaction occurs.

- Skin prick test - A small amount food extract of a suspected food is placed in a needle and injected just below the surface of the skin on the lower arm or back. Swelling or redness at the test site shows the test is positive for an allergic reaction. A positive skin prick test and history of reaction to a food may result in a food allergy diagnosis.

- Blood test - a blood sample is taken to measure levels of food-specific IgE antibodies. Test results may be combined with a historical record of food allergy reactions for an accurate diagnosis.

- Oral food challenge - a food item that is being questioned as an allergen is given to a patient in different doses in order to see if the patient is in fact allergic to it. The patient's history, skin prick test results, and food-specific serum IgE values are used to determine whether the test is safe. Someone with severe anaphylactic responses would not likely be subjected to this test. A negative result allows the patient to introduce that food into their diet, while a positive result means the patient should continue to avoid food containing the allergen (Nowak-Wegrzyn et al., 2009).

(top)

Instructional Video

Animation of an IgE-mediated allergic reaction

(top)

Additional Information

Otsu, K., & Fleischer, D. M. (2012). Therapeutics in food allergy: the current state of the art. Current Allergy and Asthma Reports, 12, 48-54.

- Food allergies are an increasing public health dilemma, and there are no viable treatments currently available to sure people with food allergies. This article discusses approaches that are being pursued to develop treatments and allergen-specific therapies such as oral immunotherapy, sublingual immunotherapy, and epicutaneous immunotherapy. Other modalities are also being investigated that may potentially lead to the discovery of novel therapeutic options. However, many of these approaches are labor intensive and not cost-effective.

Wang, J., & Sampson, H. A. (2012). Treatments for food allergy: how close are we? Immunologic Research, 54, 83-94.

- This article discusses several promising therapeutic strategies currently being investigated. These strategies may hopefully provide long-term treatment options and potentially a cure for food allergies. Moreover, information from these studies can further advance one's understanding of the underlying mechanisms of tolerance.

(top)

References

Boyce, J. A., Assa'ad, A., Burks, A. W., Jones, S. M., Sampson, H. A., Wood, R. A., . . . Schwaninger, J. M. (2010). Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: Report of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 126(6), S1-S58.

Chafen, J. J. S., Newberry, S. J., Riedl, M. A., Bravata, D. M., Maglione, M., Suttorp, M. J., . . . Shekelle, P. G. (2010). Diagnosing and managing common food allergies. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 303, 1848-1856.

David, T. J. (2000). Adverse reactions and intolerance to foods. British Medical Bulletin, 56(1), 34-50.

Food Allergy Research and Education (2014). About food allergies. Retrieved from http://www.foodallergy.org/about-food-allergies

Food Allergy Research and Education (2014). Food allergy facts and statistics for the U.S. Retrieved from http://www.foodallergy.org/facts-and-stats

Green, P. H., & Cellier, C. (2007). Celiac disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 357, 1731-1743.

Lee, Y. M. (2012). Investigation of food allergy training and child nutrition professionals' knowledge and attitudes about food allergies (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from http://krex.k-state.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/2097/13668/YeemingLee2012.pdf?sequence=1

Marieb, E. N., & Hoehn, K. (2010). Human anatomy & physiology. San Francisco, CA: Pearson Education.

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. (2010). Food allergy: An overview. Retrieved from http://www.niaid.nih.gov/topics/foodallergy/documents/foodallergy.pdf

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. (2012). Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States - Summary for patients, families, and caregivers.Retrieved from http://www.niaid.nih.gov/topics/foodAllergy/clinical/Documents/FAguidelinesPatient.pdf

Nowak-Węgrzyn, A., Assa'ad, A. H., Bahna, S. L., Bock, S. A., Sicherer, S. H., & Teuber, S. S. (2009). Work group report: Oral food challenge testing. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 123, S365-S383.

(top)